NASA looked at the times when the O-rings failed, but excluded looking at the times when the O-rings were successful. In this graph specifically, it’s hard to find any consistent relationship between temperature and failure rate in the provided data.īut NASA management made one catastrophic mistake: this was not that chart they should have been looking at. NASA management used the data behind this first graph (among many other pieces of information) to justify their view the night before launch that there was no temperature effect on O-ring performance (despite the objections of the most knowledgeable engineers who had run many other experiments). Source: Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, 6 June 1986, Volume 1,, ( link ) Color added.

If you were the decision maker for launch and only had this graph, would you have allowed the space shuttle to launch at 31 ° F, the temperature on the day of the launch? Take a look and see if you can spot any pattern between temperature on the day of the test and O-ring failure rate. Let’s look at the data that NASA analyzed and see where things went wrong.īoth the post-disaster presidential commission report and Risk Analysis of the Space Shuttle highlighted NASA management’s use of data that showed the number of O-Ring failure incidents versus temperature before launch in tests.īelow is the key graph of the O-ring test data that NASA analyzed before launch.

Think about if you would let the shuttle launch if you knew there was a 1 in 8 chance it would fail? 1 in 100,000 chance? They measured a ~13% likelihood of O-ring failure at 31 ° F, compared to NASA’s general shuttle failure estimate of 0.001%, and a 1983 US Air Force study of failure probability at 3-6%.

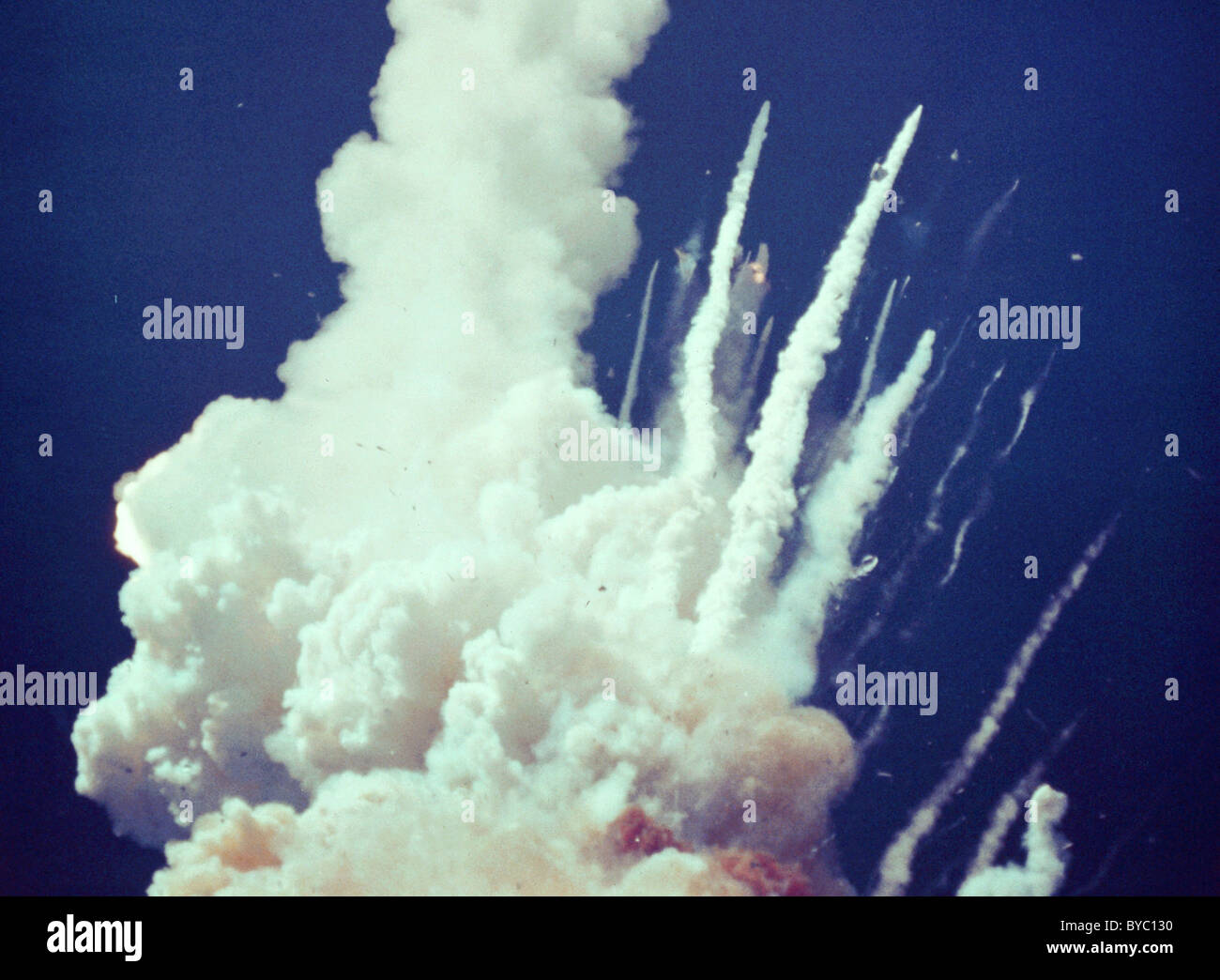

Using standard statistical techniques on previous launch data, they determined that the evidence was overwhelming that launching at 31 ° F would lead to substantial risk of failure. In 1989, Siddhartha Dalal (this author’s father), Edward Fowlkes, and Bruce Hoadley wrote a paper (“ Risk Analysis of the Space Shuttle: Pre-Challenger Prediction of Failure”) analyzing the data available before launch to determine if the failure could have been better predicted before launch. Before and after shuttle explosion (first visible signs of danger on left, just after explosion on right). NASA’s own pre-launch estimates were that there was a 1 in 100,000 chance of shuttle failure for any given launch – and poor statistical reasoning was a key reason the launch went through. This had failed due to the low temperature (31 ° F / -0.5 ☌ ) at launch time – a risk that several engineers noted, but that NASA management dismissed. The cause of the disaster was traced to an O-ring, a circular gasket that sealed the right rocket booster. Image: The Final Crew of the Space Shuttle Challenger via Wikipedia

Millions of viewers (including many schoolchildren) watched the launch live partly because Christa McAuliffe, a social studies teacher who was to be the first civilian in space, was on board. (See a video of the tragic launch here) On January 28, 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after liftoff, killing seven crew members and traumatizing a nation.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)